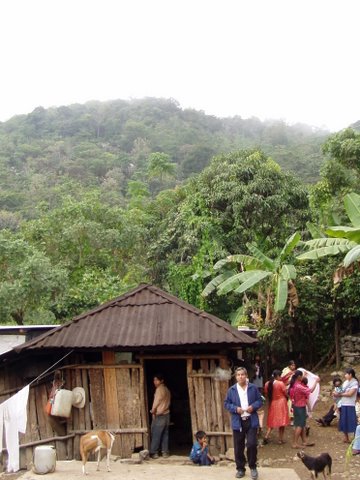

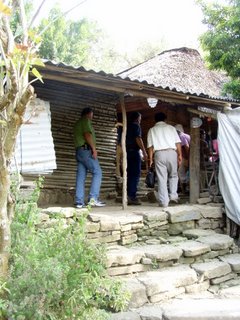

I have returned from the land of banana trees and iridescent butterflies, the land of the Huastec and Nahuatl-speaking Indians, and I am happy to report that the trip went very well, and that my father and I have returned home safely. If you’ve been watching the news lately, you’ll surely know that there’s quite a bit of conflict going on along the border of Mexico right now, and although we did see some drug cartel members along the highway in northern Tamaulipas, we got past unscathed, knowing that God was with us the whole time (although it is rather disturbing to see people with guns in Mexico who are neither military or police). As for the Huasteca Potosina, the area where we spent the week, things are much more peaceful there.

As always, a week was not enough, but I was just thankful that I was able to return there again after two and a half years absence. It was a time of renewing old friendships and making new ones, and I was also able to practice speaking Nahuatl. Most of my attempts at carrying on a conversation ended when the person with whom I was speaking uttered a sentence that went past my ears uncomprehended, and then I would resort to Spanish. I probably could have done better, but I am pleased with my progress, and of course everyone was tickled pink that I was learning their language. The Huastec dialect remains a mystery to me, but as we met a good number of Huastec people on this trip, they endeavoured to teach me some of their language as well. It is a Mayan language, entirely different from Nahuatl, and it has a very unique sound, full of glottal stops and ejective consonants. Read More