There was a time, not so long ago, when I fancied myself somewhat of an expert in the ancient Greek language. I learned the Greek alphabet shortly after learning the Roman one, and throughout childhood I studied the language slowly but surely. Upon arriving at university, the Greek professors graciously allowed me to test out of the first year of Greek, which is how I ended up taking Greek 3 during my first semester, and went on to take every Greek class that was available. So imagine my surprise, when, after all those years of acquainting myself with the language, for the first time I recently came across the fact that ancient Greek has phonemic vowel length. I had a foggy notion of Eta and Omega being “long” vowels and Epsilon and Omicron being “short” vowels, but I had chalked it up to being a weak attempt at explaining how they should be pronounced, something akin to how in my native English they say that the A in “apple” is short, whereas the “A” in “acorn” is long. Phonologically speaking, the difference between these two is a difference in quality, not quantity—in fact, the A in “acorn” is a diphthong; not even a simple vowel!

So let me define my terms before going any farther. When I say vowel length, I mean that in certain languages, it makes a difference how long you hold each vowel (length can be applied to consonants too, but for simplicity’s sake, I will stick to talking about vowels in this post). We can’t really say that English has phonemic vowel length, but imagine an ESL speaker trying to tell the difference between the words “pit” /pɪt/ and “peat” /piːt/. To a native Spanish speaker, these two words will sound exactly the same, because Spanish neither distinguishes between the quality of these vowels, nor their length. However, if this person learns to hold out the vowel in “peat” a wee bit longer, they will instantly become more understandable.

Take a look at John 3:16 in Finnish:

Sillä niin on Jumala maailmaa rakastanut, että hän antoi ainokaisen Poikansa, ettei yksikään, joka häneen uskoo, hukkuisi, vaan hänellä olisi iankaikkinen elämä. (source)

Do you see the doubled vowels? Those are the long ones, and the single vowels are the short ones. Finnish is one of many languages in which vowel length is phonemic, which is a fancy way to say that if you get it wrong, you could be changing the meaning of the word.

Another language that I have fallen in love with is Nahuatl, which was spoken by the ancient Aztecs (among others) and remains the indigenous language with the most speakers in my adopted homeland of Mexico. When I first started learning Nahuatl, the course I was using informed me that while the old classical language did distinguish vowel length, this feature (at least in the Huasteca region) was on its way out, and that learners need not worry their pretty little heads over trying to remember which vowels are long and which are short (my paraphrase). And I thought no more about it until recently, when I began to dig into the classical language.

I began to get curious. What if vowel length really is still a thing in modern Huasteca Nahuatl? With my ear now tuned to hear those little details, I began listening more carefully to the native speakers, and to my delight, I discovered that vowel length is very much still alive, at least in my home state of San Luis Potosí. If you are sceptical, the next time you meet a native Nahuatl speaker, ask them to pronounce for you the words for “man/person” and “woman,” and listen very carefully. The first word is tlākatl, and the second one is siwātl, using a macron (overline) to indicate the long vowels. The stress is on the first syllable in both of these words, but in tlākatl the first syllable is long, whereas in siwātl, the second syllable is long, which may sound a bit odd to ears trained to hear stressed syllables lengthened and unstressed syllables shortened.

As I got further into this, I realised that this explains a phenomenon I noticed in the Huasteca years ago. As I listened to people speaking Nahuatl, I heard what seemed to be a ratta-tat-tat rhythm in their speech (for lack of a better description), and I now believe that this is due to the alternation between long vowels and short vowels. Think of it like Morse code—a rhythm of short and long pulses, moving the words along.

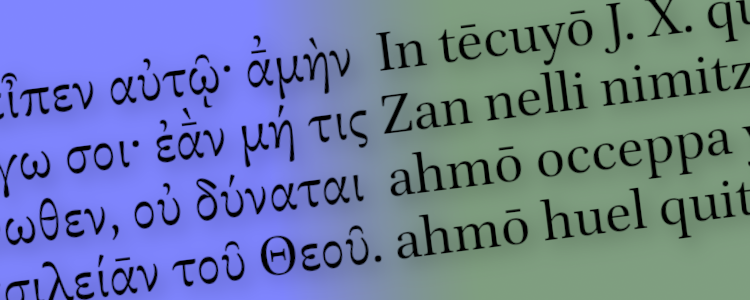

Going back to ancient Greek, it is true what I had read about the long and short vowels: Η [eː] and Ω [oː] are always long, and Ε [ε] and Ο [o] are always short. The remaining vowels, Α, Ι, and Υ can be either short [a, i, y] or long [aː, iː, yː]. If one of these vowels has a circumflex accent and/or a subscript Iota, it is long (ᾳ, ᾶ, ῖ, ῦ), and if it has neither of these things, a macron is needed to distinguish whether it is long (ᾱ, ῑ, ῡ). There is more to it, of course, which I encourage you to research further if this tickles your fancy as it does mine. I recommend this video by Luke Ranieri about the pronunciation system he devised.

So how important is vowel length, and should language learners worry about it? I think the answer depends on the language in question. The Finnish have deemed it worthy of inclusion in their everyday orthography, which seems to indicate that it has a very important role in their language. In the case of ancient Greek and Nahuatl, it could be argued that vowel length is a secondary feature, and that learners of those languages will not suffer if they neglect it. However, it is phonemic in both of these languages, and thus an integral part of their respective phonological systems. Personally, I have already benefited greatly by including vowel length in my reading of Greek texts, and it is true that in Nahuatl, there are still words that are distinguished only by their vowel length, even in the Huasteca. For example, “moon” is mētstli (with a long /eː/), and “leg” is metstli (with a short /e/). Obviously, for the casual learner, context will provide the clues as to whether moons or legs are being talked about, but if you are serious about learning to speak Nahuatl as the Nahuas do, I think you should take vowel length into account. And it’s really not that hard. Just be sure to mark it somehow—whether with macrons, doubled vowels, or colons—and practice, practice, practice!

What about Greek? Didn’t Greek lose phonemic vowel length somewhere along the way? Yes, in the early Byzantine period the Greek language lost this feature, just as the daughters of Latin did, and native Greek speakers today pronounce all vowels with the same length.

For this reason you may be tempted to brush off vowel length in Greek as unnecessary trivia, and make no effort to learn which vowels are long and short. However, if you plan to get into ancient Greek poetry (which is something I would very much like to do), it is in your best interest to learn it, because the ancients, instead of basing their poetic structure on stress patterns as in English, based it on patterns of long and short vowels. Also, if you are interested in learning to pronounce the ancient Greek tones (another fascinating area of phonology outside the scope of this post), you will find that the tones and vowel lengths go hand in hand to create the melody and rhythm of this beautiful language.

Or maybe you just want to pronounce ancient Greek as accurately as you can, and want to feel that rhythm of long ago. In any case, I hope this post has been interesting (assuming you’ve made it this far!), and has shed some light on languages you thought you knew.