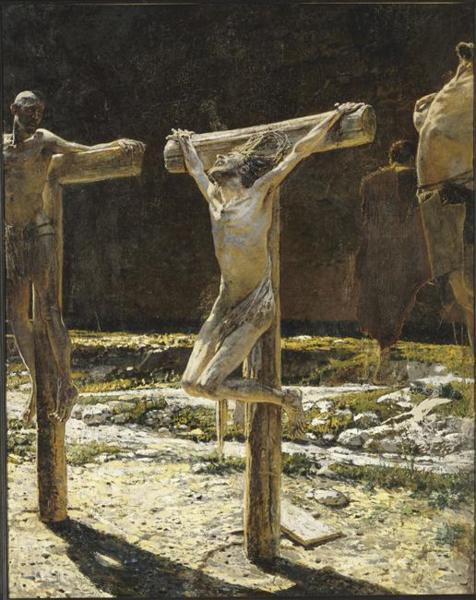

Europe certainly has its share of crucifixes. From the restaurant across from the Place Verte in Verviers, to the many representations of Christ to be found in the grand cathedrals, it seems they’re everywhere. And they all look strangely similar: The white plaque above His head with the Latin initials “I.N.R.I.,” the bearded, near-naked figure with a neutral facial expression—seemingly dead already. And I daresay that after seeing this picture so many times, the scene has long since ceased to move me.

But this time was different. I was in the section of the Orsay Museum dedicated to the work of the Naturalists, a school of painters who sought to paint their subjects as accurately as possible. And as I passed my eyes over these incredibly detailed paintings, one of them halfway up the wall grabbed my attention.

There He was again: my Saviour dying on a Roman cross. But He wasn’t as I had seen Him before, emotionless and still. This time he was screaming in pain, and the horror of His fate was so evident in His face that I could almost hear those words escaping from His lips: Eli, Eli, lama sabachthani?

(“Le Calvaire” by Nikolaï Gay, Musée d’Orsay, Paris)