The goddess worshipped at the ancient Roman-British resort Aquæ Sulis was none other than Sulis Minerva, an entity based on the Roman goddess Minerva but having characteristics of the Celtic goddess Sulis. When the Romans happened upon the hot springs there, they naturally thought of Minerva as the one who made hot water bubble forth from the ground, and when they found that the natives regarded Sulis as the keeper of the spring, they saw a chance for religious unity.

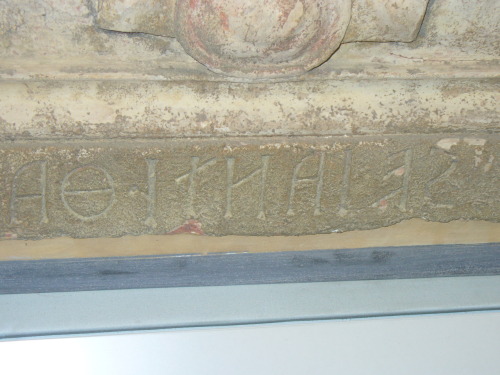

Travelers from all over the Roman Empire visited the magnificent baths and the settlement that grew up around them, and many took part in a unique method of prayer to the goddess. Instead of voicing their prayers aloud, they scratched the words upon a flattened piece of lead or pewter, then folding it up and throwing it into the Sacred Spring. Although one has been found written in the British Celtic language, most were in Latin. I found this very interesting, but I was shocked when I began reading the prayers themselves. Instead of addressing their goddess with reverence, the prayers were stated in a very straightforward way, in a language that was almost commanding. And more striking than this was that nearly every prayer was a curse. “I curse him who has stolen my hooded cloak, whether man or woman, whether slave or free, that…the goddess Sulis inflict death upon…and not allow him sleep…now and in the future,” such were the inscriptions on these petitions to the goddess.

How could these people be so bold, and so cruel? Perhaps the boldness had to do with the privacy that this medium afforded them. They could be confident that no human eyes would ever read those words (so they thought), and they trusted that Sulis Minerva would read them and deliver the vengeance that they sought. But why such cruelty? We may never know, but I dare say that while we might never dream of praying to our God to curse other people, thoughts of ill-will do cross our minds at times.